Tattoos in the USA

In the 1890s, American socialite Ward McAllister said about tattoos: “It is certainly the most vulgar and barbarous habit the eccentric mind of fashion ever invented. It may do for an illiterate seaman, but hardly for an aristocrat.”

In the 1890s, American socialite Ward McAllister said about tattoos: “It is certainly the most vulgar and barbarous habit the eccentric mind of fashion ever invented. It may do for an illiterate seaman, but hardly for an aristocrat.”

The most popular designs in traditional American tattooing evolved from the artists who traded, copied, swiped and improved on each other’s work. The developed a series of stereotyped symbols that were put on soldiers and sailors of both World Wars. Many designs represented courage, patriotism, defiance of death, and longing for family and loved ones left behind.

The earliest records are from ship’s logs, letters and diaries written in the early 19th century.

Several tattoo artists found employment in Washington, DC during the Civil War. The best known tattooist of the time was German born Martin Hildebrandt, who began his career in 1846. He traveled a lot and was welcomed in both the Union and Confederate camps, where he tattooed military insignias and the names of sweethearts. In 1870, Hildebrandt established an “atelier” on Oak Street in New York City and this is considered to be the first American tattoo studio. He worked there for over 20 years and tattooed some of the first completely covered circus attractions, including his daughter Nora.One of the first professional American tattoo artists was C.H. Fellowes who was believed to have followed the fleets and practiced his art on board ship and in various ports.

Several tattoo artists found employment in Washington, DC during the Civil War. The best known tattooist of the time was German born Martin Hildebrandt, who began his career in 1846. He traveled a lot and was welcomed in both the Union and Confederate camps, where he tattooed military insignias and the names of sweethearts. In 1870, Hildebrandt established an “atelier” on Oak Street in New York City and this is considered to be the first American tattoo studio. He worked there for over 20 years and tattooed some of the first completely covered circus attractions, including his daughter Nora.One of the first professional American tattoo artists was C.H. Fellowes who was believed to have followed the fleets and practiced his art on board ship and in various ports.

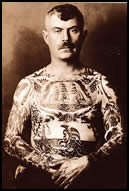

Frank DeBurdg, along with his wife Emma, were a fully tattooed husband and wife exhibit.

The pair were tattooed in New York by Samuel O’Reilly, who later invented the electric tattoo machine.

Along with the usual designs, patriotic symbols etc. Frank and Emma displayed tattoos that showed their bond and devotion to each other. Frank wore a beautiful scroll inscribed with the words “For Get Me Not”, held up by a pretty young woman with the name “Emma”, underneath. Emma bore the names “Frank” and “Emma”in prominent view.

They are best known however, for their religious themes with both Frank and Emma exhibiting exquisite biblical scenes as part of their gallery of tattoos.

Frank’s back was covered from shoulder to shoulder with the “Mount Calvary” crucifixion scene. Emma’s back displayed an even more impressive reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s “Last Supper”. Meticulously done down to the most minute detail. After exhibiting in the U.S. during the mid 1880’s the DeBurdg’s traveled abroad and enjoyed even greater success throughout Europe.

The 1897 article in The Strand magazine entitled Pictures in the Human Skin by Gambier Bolton is an excellent overview of the tattoo scene of the late 1800’s.

Samuel O’Reilly opened a tattoo studio at 11 Chatham Square, in the Chinatown area of the Bowery in 1875. At this time, tattooing was done by hand. The tattooing instrument used by Hildebrandt, O’Reilly and contemporaries was a set of needles attached to a wooden handle. The tattoo artist dipped the needles in ink and moved his hand up and down rhythmically, puncturing the skin two or three times per second. The technique required great manual dexterity and could be perfected only after years of practice. Tattooing by hand was a slow process, even for the most accomplished tattooists.

In addition to being a competent artist, O’Reilly was a mechanic and technician. Early in his career he began working on a machine to speed up the tattooing process. He reasoned that if the needles could be moved up and down automatically in a hand-held machine, the artist could tattoo as fast as he could draw. In 1891 O’Reilly patented his invention and offered if for sale along with colors, designs and other supplies.

Tattooing in the USA was revolutionized overnight. O’Reilly was swamped with orders and made a small fortune within a few years. He used to travel to tattoo wealthy ladies and gentlemen who didn’t want to go to his Bowery studio.

By 1900 there were tattoo studios in every major American city. Designs for tattoos were being produced for tattoo artists that didn’t draw well. When O’Reilly died in 1908, Wagner took over the Chatham Square studio and he patented his own improved electric tattooing machine. Sailors continued to be his customers, and Wagner’s business got a boost in 1908 when US Navy officials decreed that “indecent or obscene tattooing is a cause for rejection, but the applicant should be given an opportunity to alter the design, in which even he may, if otherwise qualified, be accepted.” When Wagner was interviewed by the newspaper PM in 1944, he estimated that next to covering up the names of former sweetheart, the work which brought him the most money over the years had been complying to the Naval order of 1908.O’Reilly took on an apprentice named Charles Wagner and during the Spanish-American War in 1898, O’Reilly and Wagner worked overtime as sailors lined up to be tattooed with images symbolizing their service in the war. At that time over 80% if the enlisted men in the US Navy were tattooed.

By 1900 there were tattoo studios in every major American city. Designs for tattoos were being produced for tattoo artists that didn’t draw well. When O’Reilly died in 1908, Wagner took over the Chatham Square studio and he patented his own improved electric tattooing machine. Sailors continued to be his customers, and Wagner’s business got a boost in 1908 when US Navy officials decreed that “indecent or obscene tattooing is a cause for rejection, but the applicant should be given an opportunity to alter the design, in which even he may, if otherwise qualified, be accepted.” When Wagner was interviewed by the newspaper PM in 1944, he estimated that next to covering up the names of former sweetheart, the work which brought him the most money over the years had been complying to the Naval order of 1908.O’Reilly took on an apprentice named Charles Wagner and during the Spanish-American War in 1898, O’Reilly and Wagner worked overtime as sailors lined up to be tattooed with images symbolizing their service in the war. At that time over 80% if the enlisted men in the US Navy were tattooed.

During World War II, Wagner was arraigned in New York’s Magistrate’s Court on a charge of violating the Sanitary Code, he told the judge he was too busy to sterilize his needles because he was doing essential war work: tattooing clothes on naked women so that more men could join the Navy. The judge must have felt that this was a reasonable defense. He fined Wagner ten dollars and told him to clean up his needles.

During World War II, Wagner was arraigned in New York’s Magistrate’s Court on a charge of violating the Sanitary Code, he told the judge he was too busy to sterilize his needles because he was doing essential war work: tattooing clothes on naked women so that more men could join the Navy. The judge must have felt that this was a reasonable defense. He fined Wagner ten dollars and told him to clean up his needles.

Wagner was the first American tattoo artist who successfully practiced the cosmetic tattooing of women’s lips, cheeks and eyebrows. He also tattooed dogs and horses so they can be identified in case of theft. He was also known to be able to combine and organize several small designs to make a larger harmonious pattern.Wagner estimated that during his career he had tattooed tens of thousands of individuals, including over fifty completely covered circus and sideshow attractions. His clients included people listed in the social register. There are photographs in formal evening attire, complete with top hat and boutonniere, tattooing an elegantly attired society lady.

Wagner continued to tattoo until the day of his death on January 1, 1953. He was 78 years old and had worked as a professional tattoo artist for over sixty years. After his death the contents of his studio was hauled off to the city dump. All his original drawings were destroyed. He had tattooed thousands of individuals and hundreds of tattoo artists admired his designs and drew from variations of them. Today he is recognized as a major influence in the classic American style of tattooing.

Tattoos also have been recently linked to the American fine art world in a number of ways. One of tattoos most significant ties to the mainstream art world is the profusion of academy trained artists entering the profession. One late 1980’s estimate placed the number of trained artists per year as having doubled as compared with those who graduated in the 1970s. Even though the number of galleries also grew within that period, art schools and programs were turning out more trained artists than the mainstream art world could absorb. Within this climate it is not surprising that art school grads have migrated into the tattoo profession. As a result, the techniques acquired in various art programs influenced the creation of new tattoo styles such as New Skool and Bio-Mechanical, as well as a commitment to innovation and experimentation.

Tattoos also have been recently linked to the American fine art world in a number of ways. One of tattoos most significant ties to the mainstream art world is the profusion of academy trained artists entering the profession. One late 1980’s estimate placed the number of trained artists per year as having doubled as compared with those who graduated in the 1970s. Even though the number of galleries also grew within that period, art schools and programs were turning out more trained artists than the mainstream art world could absorb. Within this climate it is not surprising that art school grads have migrated into the tattoo profession. As a result, the techniques acquired in various art programs influenced the creation of new tattoo styles such as New Skool and Bio-Mechanical, as well as a commitment to innovation and experimentation.

Body ornamentation, especially tattooing, was spread among Western societies when soldiers and sailors returning from conquest and trade imitated the practices they had seen among the indigenous people of Asia, Africa and the South Pacific. Working class men in Europe and America wore tattoos primarily as a symbol of tough masculine pride throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. However, a revival of interest in body modification in Western industrialized societies in the late twentieth century is associated more with domestic youth culture movements than with the foreign origins of such practices. The Beatniks of the 1950s and Hippie movements of the 1960s turned to Asian tattooing techniques as a personal expression of spiritual and mystical body aestheticism. Conversely, working-class young people of the Punk movement in the late 1970s and 80s used tattoos and piercing as symbols of rebellion in an explicit political protest against their feelings of imprisonment in society’s rigid class structure and values.

Body ornamentation, especially tattooing, was spread among Western societies when soldiers and sailors returning from conquest and trade imitated the practices they had seen among the indigenous people of Asia, Africa and the South Pacific. Working class men in Europe and America wore tattoos primarily as a symbol of tough masculine pride throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. However, a revival of interest in body modification in Western industrialized societies in the late twentieth century is associated more with domestic youth culture movements than with the foreign origins of such practices. The Beatniks of the 1950s and Hippie movements of the 1960s turned to Asian tattooing techniques as a personal expression of spiritual and mystical body aestheticism. Conversely, working-class young people of the Punk movement in the late 1970s and 80s used tattoos and piercing as symbols of rebellion in an explicit political protest against their feelings of imprisonment in society’s rigid class structure and values.

Flash refers to drawings of tattoo designs that are commonly found on tattoo studio walls. Flash comes in two varieties, standardized images that are sold commercially, or images drawn by tattoo artists themselves.The practices and conventions of the fine art world have infused the profession of tattooing. While tattoos have long been recognized for their aesthetic value within tattoo communities, defining moments in tattoo art’s legitimization process only began to occur in 1995, when Soho’s The Drawing Center, a prestigious non-profit art institution presented ΓÇÿΓÇÿPierced Hearts and True Love: A Century of Drawings for Tattoos.” This exhibition of Western tattoo flash and its Asian influences marked the first major New York City tattoo exhibition under the distinguished heading of art. When displayed within a gallery context, the meanings and functions of the objects were recognized as having aesthetic value.

Flash refers to drawings of tattoo designs that are commonly found on tattoo studio walls. Flash comes in two varieties, standardized images that are sold commercially, or images drawn by tattoo artists themselves.The practices and conventions of the fine art world have infused the profession of tattooing. While tattoos have long been recognized for their aesthetic value within tattoo communities, defining moments in tattoo art’s legitimization process only began to occur in 1995, when Soho’s The Drawing Center, a prestigious non-profit art institution presented ΓÇÿΓÇÿPierced Hearts and True Love: A Century of Drawings for Tattoos.” This exhibition of Western tattoo flash and its Asian influences marked the first major New York City tattoo exhibition under the distinguished heading of art. When displayed within a gallery context, the meanings and functions of the objects were recognized as having aesthetic value.

Tattoos have not only risen in status to become popular and acceptable, in some milieus, tattoos have achieved an elevated degree of aesthetic value. Tattoo art and artifacts have value. Tattoo, a previously ignored and marginalized practice, is undergoing a process of cultural re-inscription. New meanings of tattoo are being generated by exhibitions that reframe tattoos as art. Recent international exhibitions in American galleries and museums suggest that cultural experts are now speaking on behalf of tattoo culture.In 1999, New York City’s South Street Seaport Museum hosted an exhibition entitled ΓÇÿΓÇÿAmerican Tattoo: The Art of Gus Wagner” at the same time as the American Museum of Natural History presented ΓÇÿΓÇÿBody Art: Marks of Identity” which prominently included tattooing. Although these exhibitions differed in content and scope they shared one essential commonality: the designation of tattoo as art in an ethnographic and historical institutional context. Alan Govenar, tattoo historian, researcher, and collector, described ΓÇÿΓÇÿBody Art” as ΓÇÿΓÇÿa major breakthrough for the museum to show its outstanding collection and to create a context where that work could be understood.

Some contemporary cultural anthropologists have interpreted tattooing as an integral part of a larger phenomenon of body modification, including branding, scarring and piercing, inspired by the global disintegration of cultural frontiers.